- Home

- Hazel Rumney

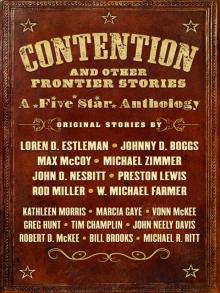

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Page 3

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Read online

Page 3

That Army man knew everything. The crowd stopped booing. The old man said, “The umpire is correct.”

“So,” I said, just to make sure I understood everything. “The score is now 9-to-8, with two outs?”

“Yes.”

I grinned. The chaplain let McSorely climb over the fence and fetch the ball, and I got ready as Millers shortstop Rotten Willie took his place inside the batter’s lines.

Again, I trotted to talk to my hurler. “Hey,” I argued. “They gave us a good game. Those folks won’t be disappointed now. This’ll be a game they’ll remember, and there won’t be shame in the Millers losing. So don’t be a softhearted sucker.”

Masterson nodded. I went back to catch him.

The crowd roared. Masterson threw a pitch at the waist that the chaplain called a strike. I had to dive to snag Masterson’s next pitch—that’s how bad it was—and heard the ump yell, “Strike two.”

I dusted myself off. Rotten Willie had swung at that pitch? It made me laugh.

Masterson bounced the next one in front of the plate, but Rotten Willie did not swing. The crowd fell silent. Sweat poured down Rotten Willie’s cheeks. Masterson began his windup and fired another pitch. This was a ball, too, way off the plate. Rotten Willie swung. And somehow, his bat connected and sent the ball over Silent Cobb’s outstretched hands as he leaped toward his left. But the professor was running on contact, backing up Cobb, and he snagged the ball in shallow left field on the second bounce.

Contention’s man on third touched home, turned, and waited. That tied the score, but we could win in extra innings. All I had to do was catch the professor’s throw and tag Cartwright out. Winning meant a lot to me. So did the money the Widow Kieberger was stealing.

I saw the baseball clearly. Then, out of the corner of my eye, I spied that little urchin, who still didn’t have shoes, still looked dirty, and still clutched that ball he had let Silent Cobb hold the day we got in. I caught the professor’s throw. The Contention player behind me yelled for Cartwright to slide. Cartwright slid. I saw the face of the woman with the parasol. I heard the kid yell, “Slide, Cartwright, slide!” I glimpsed the old man. And I imagined seeing a woman and some men leaving the alley that ran alongside Contention City’s bank. I had real good eyesight and imagination. You need that when you play catcher. I brought the ball down.

“Safe!” the chaplain yelled. “Safe! The runner is safe. The Millers win!”

The place turned into bedlam. Major Perry and his boys exploded off the bench and poured beer on Rotten Willie’s head. The folks in the grandstands cheered and sang and sang and cheered. And they cried.

I couldn’t argue. Cartwright’s toe touched the plate just before I tagged his knee. I made certain of that.

As we shook hands with our valiant opponents, those folks in the stands cheered us, too. A few of us cried, as well.

Even when Major Perry collected our bats, balls, and equipment, my Zephyrs just smiled. A wager’s a wager. We weren’t welshers. I handed Major Perry a hundred-dollar note, too.

“What’s this for?” the major asked.

“Well, some of the folks in this town look like they could use it.”

Tears welled in his eyes. “Our citizens will need this money far more than we shall need your bat-sticks and baseballs, sir, for our future . . .”

That’s when somebody shouted about something going on at the bank.

So, there we sat, waiting for the train to take us up to Benson, sipping hot beer and trying to keep the dirt sifting down from the roof from turning our drinks to mud. Caleb Cartwright came inside, nodded at us, downed a tequila at the bar, and said that the robbers had made off with twenty-three-thousand dollars.

“That’ll finish Contention City,” the barkeep said.

“I’ve already found a job in Globe,” Cartwright said. “Baseball team’s not that good, but it’s baseball.” When Cartwright pulled out a coin, the barkeep said, “No, it’s on me. Loved watching you play these past few years. Maybe I’ll get a job in Globe, too.”

As he walked outside, Cartwright told us we played a fine game, said he thought he was out for sure when he had started his slide.

Twenty-three-thousand dollars. The professor ciphered in his head. “Ninety-two-hundred dollars for us. That takes the sting out of losing.”

“When do we meet the Widow Kieberger?” Hank asked. He spoke too loud ’cause the barmaid was bringing us another round.

“Joyce got married?” Her face beamed.

“Joyce?” I said.

“Joyce Kieberger. Is that who you was talkin’ ’bout? I used to work with her. She got married?” The rest of what she heard saddened her. “And her new husband up and died?”

I needed that bourbon. “The Widow . . . Joyce . . . Missus Kieberger. She wasn’t married . . . while she was . . . working . . . here?”

Hank drank his beer and Skyrocket McSorely’s, too. Both looked as sick as I must’ve.

The barmaid lowered her voice. “Goodness. Girls in our line don’t get married. Not in the towns where we ply our trade.” She started to leave, turned, and said, “If you see Joyce, tell her Dixie says congratulations—and more congratulations if her late husband was real rich.”

When she stood back at the bar, I muttered something that the professor told me was anatomically impossible.

The urchin stuck his head in what once was a doorway to the saloon. “Train’s coming in,” he said. The whistle affirmed his statement.

“You think that widow will pay us?” McSorely asked.

I gave him the look I give Hank when he swings at pitches a mile over his head.

“You think,” the professor asked, “that she might somehow let word out that we were in on this heist?”

“A few telegraphs,” Hank said, “and they’ll figure it out themselves.”

We made a beeline for the depot, passing the Contention City Base Ball Field. Hank, McSorely, Masterson, and I took a detour, but we got on the train all right, and soon were steaming as far away as we could from Major Perry’s ballists, especially Contention’s right fielder.

As we tried to relax in the smoking car, Masterson sighed. “The thing is, we could have beaten those boys. Had them beaten.”

I shook my head disgustedly. Masterson had been among the first to go soft.

“Won’t get another chance now,” Hank lamented. “Contention City’s done for. That team will always be remembered as going undefeated in seven seasons and one game.”

Cobb leaned toward me. “And you owe us our dough. You said we’d be paid win or lose.” That silent third baseman never shut up.

Hank pointed this out: “The deal was we’d get paid when the Widow Kieberger paid Skip.”

“When we get to Tucson . . .” I began, the idea coming over me and making me feel as good as that urchin and those other Contention City folks must have felt after watching their team win that game. “Why don’t we try to play Tucson’s town team?”

“With what?” the professor said. “Thanks to your bet, we lost our bat-sticks, balls, and all our equipment to the Millers.”

Hank chuckled. So did I.

“No,” I said. “The marshal and major led that posse off as soon as they heard about the bank being looted. Most of the Millers rode out with him.”

Hank added: “Left their equipment and ours, too, at the field. We picked it up. All of it. Put it in the baggage car.”

“Major Perry won’t be using those bat-sticks to club anyone to death ever again,” Kent Masterson said.

“Like that ever happened,” Skyrocket McSorely said. “I’d like to use my bat-stick on that widow’s noggin.”

“Now, now,” I said. “You don’t want to wind up in Yuma. And I’m serious. Let’s play Tucson’s team when we get there.”

“Hey,” Masterson said. “Maybe Benson has a team, too.”

“Most towns do,” Silent Cobb said. “We could also play Tombstone.”

I pointe

d out: “After we beat Tucson, we should leave the territory. Unless you want to play prison baseball.”

“I bet,” Hank said, “we could play the Fat Fellows in Silver City.”

McSorely said: “And there are plenty of town teams in Colorado.”

Cobb and the professor didn’t look so angry now. Cobb even admitted, “We do have a good team.”

“We might even best the Millers’ record,” McSorely said.

Masterson grinned. “The American Zephyrs. For real, this time.”

“No,” I said. “We use that handle, the major and marshal would undoubtedly find us, and even if those boys didn’t beat anarchists to death with bat-sticks, they surely would stove in our heads.”

We thought.

Long before the train pulled into Benson, we had our name.

The American Suckers had a nice ring to it.

Johnny D. Boggs is a seven-time Spur Award winner. The Little League baseball coach, umpire, and former sportswriter lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, with his wife and son. His website is JohnnyDBoggs.com.

EDDIE AND THE STRANGER

BY VONN MCKEE

Sheriff “Fat Jack” Jennings didn’t even look up from his newspaper when two cracks of gunfire echoed from up the street. The man seldom heaved himself out of his chair unless things got truly ugly. It was said there’d been seventy-two murders in Pioche, Nevada, before the first death by natural causes occurred, and already the cemetery was the fastest growing part of town.

Pioche was young and cocky, swarming with glinty-eyed speculators who laid claim to swaths of Treasure Hill outside town, hoping for a piece of the silver mining action. For every investor, there were hundreds of threadbare laborers, risking their lives in the creaky shafts underneath the mountain for a dollar or two a day. Common thieves, claim jumpers, and general troublemakers rounded out the town’s population.

Hearing three more gunshots, Fat Jack huffed and slapped the paper on the desk. He shoved his chair back. “Spence, I s’pose we’d better go check on things. Sounds close. Lynch’s Saloon, maybe.”

Deputy Spencer Melton had just finished passing out plates of cabbage and beans to the inmates. The Pioche jail hadn’t been empty since the day it was built. “Well, if there’s any left standing, I don’t know where we’ll put ’em,” he said, hanging up the oversized key ring.

“Just shoot ’em. That’s my creed.”

Indeed, Fat Jack had lead-poisoned plenty of men since he took office. And he had taken bribes from plenty others who could buy their way out of his jail. He was called “Fat Jack” for the bulk of his wallet and not necessarily his middle-aged paunch.

“You’d think these hell-raisers would eventually all shoot each other dead,” said Spence, grabbing his hat. “Wouldn’t be nobody left to bury ’em, I guess.”

“Wouldn’t that be nice?” said Fat Jack, slamming the door behind them.

The sheriff guessed right. Two men carried a blood-soaked body, boots first, through the doors of Lynch’s Saloon and crossed the crowded street to the undertaker’s office. A man, surrounded by a ragtag group of miners, sat on the edge of the boardwalk with his head in his hands.

“Who’s the shooter?” Fat Jack asked, to nobody in particular.

“Him,” said John Lynch from the doorway, pointing to the hunched figure on the boardwalk. The saloon owner looked disgusted, maybe even a little pale. “The two of ’em got in a tussle over something. Couldn’t hear what about. They’d had a few . . . well, too many, I reckon. This one turned mad out of his head. Grabbed somebody’s pistol and shot the fellow twice in the face. Then . . .” Lynch wiped his brow and blew out a deep breath. “Then he stood over the man, who was done dead, for sure. Shot him a few more times square in the chest. Out of control, he was. Just kept shooting. Biggest damn mess I ever saw. And I’ve seen some.” Lynch motioned over his shoulder. “How the hell I’ll get that floor cleaned up, I don’t know. Then there’s the bullet holes.”

Fat Jack and Spence stood at each side of the crazed killer, who was no more than a small heap.

“What’s your name?” Fat Jack grabbed the man’s shoulder and straightened him up so he could see his face. He was a miner, slightly built—probably a Basque—wearing a shabby flat-crowned hat. His face, coat, and overalls were embedded with dark reddish mine dust. His eyes were squeezed shut and he didn’t answer.

“Maybe he don’t speak English,” said Spence, turning to the other miners. “Who is this fella? Somebody speak up.”

The laborers looked sorrowful, until one said, “That’s Eddie. He would not . . . it is not like him to do this kind of thing.”

“I did not . . .” The quavering, pitiful protest came from Eddie. “I did not . . . I did not,” he continued weakly. His small grimy face was streaked with tears.

“Well, Shorty, a saloon full of men say you did.” Fat Jack grabbed Eddie’s arm and dragged him to a standing position. The miner couldn’t have stood more than five feet tall. “Keep your gun on him, Spence. He looks like a tough one.”

Fat Jack grinned, revealing a gap between his front teeth. The sheriff somehow managed to maintain a frown, even when smiling.

Edarto Luken—or Eddie—was by far the quietest prisoner in the Pioche jail, except for when he had nightmares. The first night, he woke up the whole place with his thrashing and babbling.

It would be a pretty cut and dried conviction, Fat Jack thought, although it would be over a week before the next court date. The sheriff was always a little peeved when he had to follow legal procedures. If the little miner had put up a fight, there would have been grounds for putting a bullet in him and ending the matter.

“What came over you, Eddie, that you went and killed a man?” asked Fat Jack, locking up a cell after the release of a sobered-up drunk. Eddie had a cell of his own at Deputy Spence’s request. He didn’t think the little man would last long with any one of the current cellmates.

Eddie sat on his narrow bunk. He’d washed up—his face, at least—and Fat Jack guessed him to be about twenty. “Sheriff, I did not commit this terrible act.”

“Yeah, you keep saying that. If you didn’t, then you wanna tell me who did? You were the only one standing over that fella with a gun in your hand.”

Eddie rose and walked to the cell door. He wrapped his fingers around the bars and looked imploringly at the sheriff. “Sheriff, I will be needing—what do you call? One who argues the law.” Fat Jack cocked an eyebrow.

“A lawyer? You wanna get a lawyer? You think you got a prayer of getting off with murder?”

“You must believe me. I was not the one responsible! It was . . . someone else.”

“And just who might that be?” The sheriff was interested to see where this was going. Eddie swallowed hard.

“It is hard to explain. Sheriff, I am not a man who would do this. You may ask anyone at the mines.”

The sheriff recalled hearing the miners outside the saloon saying more or less the same thing. Surely, Eddie did not believe he was innocent! He let the man keep talking.

“I do not myself touch strong drink. I do not believe in harming another. I am a religious man, Sheriff Jennings.”

Fat Jack was getting impatient with the little man. “Five shots, you liar. At close range. That man’s face and chest were shot to a pulp when you got through with him.”

Eddie buried his face in his dirty sleeve, choking back sobs. After a minute, he looked Sheriff Fat Jack Jennings straight in the eye. “I am not the one who fired the shots. It was . . . it was the stranger.”

Fat Jack had heard a lot of wild tales. A man behind bars would say about anything to save his hide. This was a new one. “The stranger? Didn’t hear anybody mention a stranger.”

Eddie gripped the bars again and wedged his face between them. “The stranger is a terrible man. He has done terrible things. Things I would never do. I swear this to you,” said Eddie, placing a hand over his heart, in oath.

“Okay, let’s sa

y I buy your story so far. Where do you reckon this stranger is now?”

A look of misery washed over Eddie’s face. He slowly moved his hand from the left side of his chest to the right.

“He is here,” he said.

The sky outside the sheriff’s window was gray with the approaching dawn. Water for coffee heated in a pot on the wood-stove.

“Gawdamighty, Sheriff. Can’t you do something about this little Turk, or whatever he is? It’s hard enough to sleep on a board without some fool jabbering in his sleep.” Hobie Smith was a frequent guest at the Pioche jail due to his love of a good brawl. He gingerly rubbed a swollen eye with his big paw.

Fat Jack was good and tired of Eddie’s nightmares and the complaints from the other prisoners. He grabbed a fire poker and stalked to the back, then slammed the poker a couple of times against the bars of Eddie’s cell. “Wake up! Enough of that caterwauling!”

Eddie jumped up from his bunk and looked around wildly. Like a storm cloud swallowing the sun, his face turned angry and his eyes sparked hate. He rushed to the cell door and poked his skinny arms through the bars, reaching to grab Fat Jack by the throat. His small hands were locked into rigid claws. “Get over here, you coward! I’ll squeeze your fat neck to mush.”

Fat Jack took a step back, the iron poker hanging forgotten in his hand. “Eddie?”

Eddie strained to get a grip on the sheriff. His hair stuck up in messy spikes, framing his frightful countenance. Profanities in at least two languages spewed from his mouth. Apart from Eddie’s tirade, the jail was dead silent. Fat Jack’s brow furrowed as he considered his next move. Eddie continued to claw the air between them. The sheriff propped the poker against the wall behind him. He lowered his head and charged toward the cell door, with his big fist drawn back. He connected neatly with the bottom half of Eddie’s face, but not before the miner grabbed his shirt. The jail echoed with the sounds of ripping fabric, the smack of the punch, and Eddie’s body sprawling heavily onto the bunk behind him. He lay motionless, eyes closed.

Fat Jack picked up the poker and walked back to his office. He sank into his chair, waiting for his heart to slow down. On the stove, the coffee water boiled vigorously. Spence came in the door, ready for breakfast duty. He froze when he saw Fat Jack, shirt ripped, staring at the pot clattering on the stovetop.

Contention and Other Frontier Stories

Contention and Other Frontier Stories