- Home

- Hazel Rumney

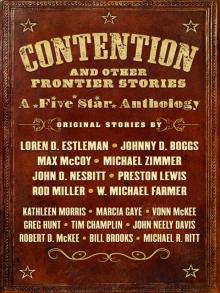

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Page 2

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Read online

Page 2

“Then we better start practicing,” I said. “And find us a southpaw hitter.”

Naturally, we did not take the train to Los Angeles. Nor did we travel to Chicago and Detroit. I did go to Denver, where I signed up Skyrocket McSorely, who played right field with a center fielder’s speed and batted left-handed. By the end of the month, we were back across the border, practicing every day for our date with the Contention Millers.

While celebrating a real fine practice on the third of May, we all got knocked off our feet. The earth shook. Hank lost six pounds. Masterson lost his breakfast. Skyrocket McSorely confessed all his sins, which sounded considerable. I cried out for my ma.

The rumble didn’t last that long, and the Almighty did not open up the earth and drop us down to Hades. The next morning, another little shake rattled our nerves, and after we found our scattered horses, I rode to Bisbee to see what had just happened.

What had happened, of course, was an earthquake. The telegraph lines were all down, so I spent some of the Widow Kieberger’s money on a stagecoach ride to Contention City.

Not that I was drunk, but what I saw and heard sobered me.

Roofs had collapsed, the whistles at the mine and mills kept blaring, and the baseball diamond lay in utter ruins. Somehow, amid all this commotion, I managed to find Major Perry. Seeing me, he shook his head, and waved at the mess behind him.

“We cannot play,” he told me. “Not on this.”

Ever seen photographs of Atlanta taken after Sherman’s boys marched through? That’s what the Contention City Base Ball Field resembled. It’s what a lot of Contention looked like. I quickly thought of this: “But you do understand that there is no refund on the deposit of our appearance fee.”

“I don’t give a whit about that, sir!” he snapped.

That earthquake was a godsend—for me.

“Why don’t we reschedule our game?” I suggested.

“Next month?” Major Perry said.

“Next year,” I said.

Yep, that was a gamble. But I had seen Contention play and my boys practice. We couldn’t beat the Millers, not with the ballists I had lined up. I also saw just what a boomtown Contention City was, and figured once she got fixed up, there might be more money to earn. I am greedy. Which, along with my temper, had cost me forty-two months in Yuma. And was why even the Beer and Whiskey League wouldn’t let me play on their teams anymore.

“You’d do that?” Major Perry asked.

This was no lie: “Major, it’ll take you a year to get this diamond, and your city, back in shape.”

I can’t call the Widow Kieberger understanding. When I met her up in Benson, she did not sound like the meek, frightened, revengeful woman I had talked to in Yuma. But eventually, reason prevailed. If we were to beat the Millers, if she was to get what she wanted, then patience, and practice, came first. She also conceded, after a second brandy, that she had yet to find a man suitable for her purposes. Turned out, I knew a fellow who would be out of Yuma in November.

After paying off my middle infielders, two outfielders, and a backup hurler, I let the rest of the boys find baseball clubs for the upcoming season whilst Hank and I took off to Galveston . . . New Orleans . . . St. Louis . . . Cincinnati . . . and even Laramie, where a couple of ballists I knew were getting out early on good behavior. From those towns and a handful of others, I sent telegraphs to newspapers in southern Arizona, letting their readers know that the American Zephyrs had won another game, making up a few details and a final score, and hoping no editor would ask for confirmation from another source.

By late October, the mercenaries that made up the American Zephyrs reconvened in Bisbee, and we crossed the border again. In early March, I sent a telegraph to Major Perry, suggesting a date to make up our ball game. He happily agreed to the date and our original terms.

Even the Widow Kieberger looked happy. I had rounded up a pretty good bunch of ballists, and that fellow I’d told her about proved mighty handy at cracking safes.

The game pitting two undefeated teams would be played on Monday, April 30. The payrolls would arrive in Contention City on the evening train on April 28. Contention’s miners and millers would not be paid until May 1.

I didn’t think another earthquake would postpone our game this time. As long as it didn’t rain . . .

We arrived on the same train as the payrolls, and the armed guards, including Contention’s right fielder/marshal, greeted us at the depot. Turns out, some of Major Perry’s ballists—when not beating town teams or clubbing some anarchist to death in his bedroom—also protected Contention’s money on its way to the bank for safekeeping till payday.

Caleb Cartwright, Contention City’s third baseman, grinned a broken-tooth smile and directed us to Mason’s Western Hotel.

That rundown adobe structure wasn’t much to look at before the earthquake, but a year ago, the windowpanes had glass, the adobe walls didn’t show straw, and the roof covered the entire hotel.

“Criminy,” Skyrocket McSorely whispered as we walked down the deserted street. “I thought you said Contention City was a boomtown.”

“The key word in that sentence,” our shortstop, Professor Anderson, said, “is was.”

The Contention Millers had won all twenty-two games last year, but every contest had been played on the road after the earthquake had destroyed their field. Though I had briefly seen the town after the earthquake, I never really appreciated the extensiveness of the damage.

After settling into our hotel rooms, we walked to the Contention City Base Ball Field to practice. On our way, a little waif sprinted out of a ramshackle jacal. He didn’t wear shoes, and I doubt if the urchin had seen a washcloth in months. “Are you the famous Zephyrs?” The boy held out a baseball.

Silent Cobb, our third baseman who hated everything and everybody, took the ball and stared at it. “Uh,” he said, “yeah”—more words than he’d spoken in two weeks of practicing.

“Gosh.” The boy snatched back the ball. “A Zephyrs ballist touched my baseball. Nobody but me will ever touch it again. Even if you beat my team Monday.”

“Your team?” Cobb just doubled his dialogue.

An old man arrived over from the other side of the street. “About all we have left in this town now,” he said, shaking all of our hands, “is our baseball team.” He said it was a pleasure to have us here, that a team with the national reputation of the American Zephyrs would be a great test for the Millers.

“We’ll see if we can compete against something other than other town teams,” said a woman in a parasol who stepped off the boardwalk to welcome us to Contention City.

“At least you’re honorable players,” said a gent in sleeve garters. “Unlike the Tigers of Tombstone.”

“They burned our bench the year before last,” the urchin informed us.

“And abused our womenfolk,” said the old man.

“We hate Tombstone,” said one of the bunch of folks greeting us.

Hank Fuller shot me a glance, and I knew he was wondering if maybe Tombstone had deserved that abuse and beating we witnessed last year.

I didn’t dwell on that, however, because a woman brought us cookies. Another resident, bless his soul, carried buckets of bottled beer. But that was nothing compared to what we saw at the Contention City Base Ball Field.

Our practice, I realized, was the first time we had played in front of spectators, excepting, just before we left Mexico, the Widow Kieberger and her safecracker and a few other rogues she’d hired. I’d played real games before smaller crowds.

“Wait till tomorrow,” one man said. “The whole city will be here. Everyone in town!”

Which is what the Widow Kieberger had said when I first met her in Yuma.

Even though we were just practicing, everyone cheered us. They whistled. It felt great, like it used to feel when I was playing years ago. A long time had passed since anyone had hollered encouraging words for me at a baseball field. I sure never heard

anything like that whilst catching for Yuma’s guards.

Then I remembered what brought us to Contention.

Just nine years back, this city had boomed after the discovery of silver. Miners found pay dirt in the hills around the town, but Contention thrived because of the stamp mills—hence their baseball team’s nickname, the Millers. The San Pedro River provided water, which most of the mining towns—including Tombstone—didn’t have. Two stamp mills had been established, the railroad arrived, the team kept winning, and life looked fine in Contention City.

We learned all this as those poor folks treated us to supper and beers after our practice.

Of course, nothing lasts forever, someone pointed out, to which Kent Masterson leaned toward me and whispered, “Like the Millers’ undefeated streak,” and grinned.

Folks, we learned, found a way to get water to Tombstone. The mines around Contention got flooded. So did the two mills, especially after that earthquake. One mill had already closed this week, and its miners were waiting to collect their last pay before moving on. Everybody knew the other mill’s days were numbered, too. The railroad had reached Fairbank a few miles south, meaning fewer folks needed to travel to Contention. The Bisbee stage line had already stopped running to Contention. Since the earthquake, folks had been leaving for better jobs, or any jobs. Once, you could hardly find an empty spot at the Contention City Base Ball Field when the Millers played. These days, the grandstands could seat twice the town’s current population.

The team had struggled, as well. Once, the Millers had an outstanding First Nine, a Second Nine that could beat most town teams easily, and even a Muffin Nine that played solid baseball. Now, they had ten players total, and last year they won their twenty-two games by an average of one-point-nine runs. Four of the games went extra innings. One game they won by forfeit. Such things never happened in the glorious days before the earthquake.

When we got back to the hotel, I had to remind the boys, even Cobb, why we came to Contention, what those thugs did to the widow’s husband, and what we could take home after beating the Millers to a pulp.

The last day of April dawned bright and sunny with no wind. We had the Millers whipped before the umpire, an Army chaplain from Fort Huachuca, called us out to flip a coin. The Millers won the toss and elected to be the home team. Masterson snickered, “That’s all they will win today.”

Indeed, it looked that way. Masterson struck out the first six batsmen he faced. We scored two runs in the first inning, and three in the second. The crowd looked like they were attending a funeral.

But, by grab, how they cheered in the bottom of the third. That’s when Caleb Cartwright singled up the middle. He didn’t get past first base.

We led 9-to-2 in the sixth inning. I could hear sobs coming from the little waif whose baseball Silent Cobb had briefly held. Major Perry hit a little grounder to third, and Silent Cobb’s throw had that brute out by a mile—till Hank Fuller dropped the ball.

“Safe,” the chaplain said.

Masterson then hit the next batsman with a pitch.

“Take your base,” the chaplain said, and I muttered an oath. Giving a batsman first base when he got hit had just become a rule in ’87. The soldier boys at Fort Huachuca knew their baseball.

The next Miller got hit, too, loading the bases, and sending me out to calm down Kent Masterson. Hank Fuller waddled over, too.

“Relax,” I told my pitcher, who wasn’t throwing as hard as he could. “Your arm hurting?”

“No.”

“Well, Hank muffed a play. It happens. Forget it.”

“I didn’t muff that ball, Skip,” Hank told me.

Masterson said: “And I know what I’m doing.”

I pulled off my cap to scratch my head.

“We can’t beat this team,” said Silent Cobb, who trotted over to take part in our discussion.

“We can beat the tar out of them,” I said. “Which we’ve been doing.”

The chaplain hollered: “Hurry up!”

Seeing my teammates’ faces, I put my cap back on. “You can’t throw this game, boys.” I felt sick.

“You did,” Silent Cobb said, and I wished he would turn mute again. “With the Brown Stockings in ’82.”

“And the Buffalo Bisons in ’79,” Hank recollected.

My ears reddened, and Hank hadn’t swung at a ball over his head this afternoon. “You . . .” I jabbed my swollen finger at Hank’s fancy lace-up shirt that the Widow Kieberger had paid for. “You remember how these Millers played ball that time we saw them. Played like hooligans.”

“You heard what the Tigers did here,” Hank pointed out.

I countered: “I heard. But I saw how this team played. Like hooligans.”

“Just like I played with the Maroons in ’86,” the professor said. He had walked over, too.

“And ain’t that why you got sent to Yuma?” Masterson said. “Beat up the umpire with your bat-stick in Prescott for calling you out on strikes?”

“Fool deserved it,” I said. “Ball was a foot outside, and low.”

“Do you want to gossip?” the chaplain yelled. “Or play baseball?”

“They beat a man’s head in,” I told my Zephyrs. “With bat-sticks. That’s why we’re playing them.”

“We’re playing them,” Hank said, too honest for his own cheating good, “for what the Widow Kieberger, that safecracker you knew in Yuma, and those gunmen she hired are doing right now.”

“Because,” I argued right back, “of what Major Perry, the town marshal, and the rest of these murdering ballists did to her husband.”

“The Millers aren’t the point,” Masterson said. “I can’t beat them . . . for their sakes.” He nodded at the practically empty stands, filled with the last of Contention City’s lovers of baseball, pretty much everybody in town.

I made the mistake and looked. I saw the little urchin, the old man, the lady with the parasol, and that redheaded strumpet who brought us all the beers we could drink at the cantina we had been frequenting. I saw their faces. The chaplain yelled again, but what struck me was the crowd. Any other city, any other team, and the spectators would be shouting louder than the umpire for us to quit chattering and play ball. They just sat, respectful, patient.

“Don’t be suckers, boys. We’re professional ballists, or once were. Let’s get out of this inning,” I said. Then I slapped the ball into Masterson’s hand and trotted off to my spot.

Caleb Cartwright hit the next pitch over McSorely’s head, and all four runners scored. It was 9-to-6.

It stayed that way till the bottom of the ninth inning. With two outs, and the Contention City faithful resigned to their fate, Major Perry singled. The professor let Contention’s marshal/right fielder’s hard roller go between his legs, and Major Perry wound up on third. Masterson then threw five consecutive balls to the Millers’ second baseman, who ran down to first base.

“It takes seven balls before he can take first,” I pointed out.

“That was in ’86, Skip,” the chaplain said. “And it was four strikes instead of three last year, and they counted walks as hits. Who knows what the rules will say next year.”

Course, I figured if the umpire knew the rule about hitting a batsman, he’d know how many balls it took to send a player to first. It was worth a chance, though. Sometimes, you get umpires who don’t know a thing. Not in Contention City, though. They used smart umpires.

I asked for time and went out to talk to Masterson. When my infielders started to join us, I yelled at them to stay put. I didn’t need my boys teaming up against me.

“Walk Cartwright,” I told Masterson.

He blinked and beamed. “You’re with us!”

“No. I want to win.”

Confusion masked Masterson’s face. “You want to put the tying run on second base, Skip?”

“Yeah, because Cartwright has power. Their shortstop hasn’t hit all game. All we need is one out.”

Masterson grinne

d. He thought he could outsmart me. “All they need is four runs. I could walk or hit Cartwright, the shortstop, and everyone else.”

“You can try to walk that shortstop, and he’ll still strike out. You can try to hit him, and he’ll dive out the way like the coward he . . .” I stopped. It sort of struck me curious that a member of the Millers could be such a coward on the baseball field and a rapscallion who beat men to death in bedrooms. But Contention wasn’t the same Contention anymore.

Something else, something better came to mind.

“You can walk in all the runs, let Contention win,” I said. “And you’d not only be a sucker, you’d be a heel. You’d be cheating all these folks here. You’d crush them. Kill them. They want to see the Millers win. Not the Zephyrs blow it. You let those boys win with walks and hit batsmen, and you’ll just disappoint everyone left in Contention City. So go ahead. Do it your way. Shame these poor folks. Walk Cartwright. If that shortstop after him can tie the score, good for him. That’s baseball.”

Knowing I had Masterson—because I’d just, for once, told the truth—I walked back, squatted, and waited for Masterson’s pitch.

It came, faster than he had thrown since the first inning. Straight across at Cartwright’s belt. Cartwright swung. I cussed. The ball once again sailed over McSorely’s head, but this one went even farther. Three runners crossed the plate, and Cartwright was coming home. The crowd stood, screaming, cheering, but the chaplain started yelling something, too. I kept waiting for McSorely to get the ball, but he just stood at the fence. I didn’t think Cartwright had knocked the ball over the fence. It couldn’t be a home run. Could it?

“Double!” I heard the chaplain. “That is a ground-rule double. Back to second, Cartwright. You—” Our umpire pointed at Contention’s second baseman. “You must return to third base.”

Now, Contention’s faithful in the stands booed the Army chaplain. Major Perry came from the bench to argue.

“Sir,” the ump said, “there is a new rule this year that states if a fair ball bounces over the fence, and that the fence is not more than two hundred and ten feet from home plate, then the hitter must remain at second base.”

Contention and Other Frontier Stories

Contention and Other Frontier Stories