- Home

- Hazel Rumney

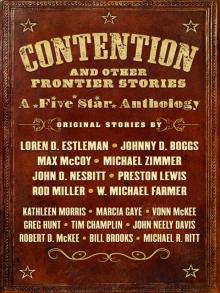

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Page 4

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Read online

Page 4

“You all right, Chief?”

Doctor William Kent sat beside Sheriff Jennings at the Capitol Saloon bar. He was not a frequent patron at the Capitol, or any saloon, but Fat Jack invited him there to ask his opinion on something.

“It’s the damnedest thing I ever witnessed.” Fat Jack wiped the beer foam from his mustache and clunked the empty glass onto the counter.

“For two days now, this Eddie fella has been switching from a meek little lamb to a bull madder than hell. I want him out of my jail. When he’s quieted down, he swears his other half should be charged with the murder. Have you heard of such? Says the stranger makes him commit acts against his will . . . that ain’t part of his genuine nature.” Fat Jack shook his head, rubbed his temples, and ordered another drink.

Doctor Kent’s brown eyes were alive with interest. “Now isn’t that something?”

“He got worse day before yesterday. He was in the middle of a nightmare, twisting around and hollering. I just meant to wake him up by banging on the door, but he jumped up ready to choke me. Maybe tear me to pieces. It’s like having two different men in the cell at different times. He’s Eddie for a few hours, then—poof!—that stranger comes outa nowhere. They’s something wrong with that boy, that’s for damn sure. You got any idea what it might be?”

“That is truly puzzling,” said Doctor Kent. “It does remind me . . . well, have you ever heard of Doctor Benedict Morel, Sheriff?”

“Nope. Was he an Englishman, like you?”

“French, actually. I read some of his papers while I was studying medicine. Morel observed patients in asylums who exhibited similar behaviors.”

“Well, maybe Eddie was one of ’em.”

“It’s doubtful. His findings were from studies conducted over twenty years ago.”

“Hmm. Before Eddie was born. And what did this Morel fella make of it?”

The doctor pressed a finger to his temple, conjuring a memory. “Blast it, what was that term? Morel had observed declining mental capacity in older patients but this was a phenomenon he saw in younger ones. Dem . . . ah! Démence précoce! That’s it!”

“Oh, well, I could have told you that.” Fat Jack laughed at his own joke. He was losing interest in the discussion and waved at someone across the room.

“At any rate, it means precocious dementia. Not terribly specific but at least he understood that it was a unique disease of the mind. Sheriff, would it be all right if I observed Mister . . . what did you say his name is?”

“Luken. Edarto Luken. Known as Eddie . . . or the stranger. Depending on the time of day, I reckon.”

Doctor Kent shook the sheriff’s hand. “I’ll drop by in the morning. Thank you for tonight’s invitation.”

As the doctor left the saloon, Fat Jack realized the man hadn’t touched his beer. “Well, no use in it going to waste.” He slid the glass over and raised it to his lips.

At Doctor Kent’s request, the sheriff again awakened the fitfully sleeping Eddie. However, he only called out his name rather than using the poker to arouse him. He wasn’t sure his heart was up to another confrontation, even if he knew it might be coming. Eddie tumbled out of the bunk, irritated, but at least not bent on murder.

Fat Jack whispered to Doctor Kent, “This here is the stranger we’re talking to. I can tell by his eyes.”

After fifteen minutes of interrogation, Eddie said, “I’ve had enough of your questions, limey.” So far, he’d given mostly rude responses.

“One more, if you’ll allow me. Your mother and father . . . did they have any . . . peculiarities? Unusual moods?”

The stranger that was Eddie looked suddenly stricken. Fat Jack thought the man was about to break down and cry.

“Mother . . .” he mumbled. “My mother.” His lower lip trembled and, sure enough, tears welled up. Before Fat Jack and Doctor Kent’s eyes, his demeanor changed. His hands slid down the bars and he seemed to melt into a frail child crouched on the floor. When he looked up, he wore the same expression as when he’d been arrested—sorrowful, crushed.

“I am so terribly sorry, Sheriff. And you . . . are you a doctor? You look like one.”

Hiram Newkirk stopped outside the sheriff’s office to adjust his collar and flatten his hair on top for the tenth time. His wiry strawberry hair was a constant bother. Suits never hung well on his gangly frame and, no matter how he fiddled, his tie and Adam’s apple were always at odds. At least, no one judged his fashion sense harshly here in the west. If anyone looked askance, it was solely because he was wearing a suit. He collected his thoughts and opened the door.

“Sheriff Jennings? I’m the lawyer you sent for. Well, not the one you sent for precisely but . . . Mister Hodge is away in California. I’m Hiram Newkirk.”

Fat Jack sized up the tall, awkward young man. “Obliged,” he said, shaking hands. “You, uh, new in town?”

“I am, sir. Not so new. I’ve been here for three months. From Indiana.”

“Might’ve seen you at the courthouse then. Well, three months. You’re a regular old-timer, by mining town standards anyhow. You’re taking some heat off of Hodge, are you? There’s lawsuits flying around this town like locusts.”

“I am aware of that. I’ve handled a dozen claim disputes already. Mister Hodge has kept me busy. But you wanted to speak to me about representing someone in a murder case?”

“Yes, murder. It should be simple, what with having several witnesses. But, well, it’s taken a peculiar turn. Ah! Doc Kent just rode up. Maybe he’d better explain it.”

“So, you’re really going to court today and arguing that Eddie can’t be held responsible for the actions of another part of who he is? This is making my head hurt.” Fat Jack plucked the key ring off the hook and turned to Hiram Newkirk and Doctor Kent, who both looked like excited puppies.

“Yes, Sheriff. It sounds preposterous but if you think of it logically, it makes perfect sense,” said the doctor. “Mister Luken has a distinct and separate entity within himself who seems to surface when he is under strain. I have interviewed both of these ‘persons,’ if you will, and found them to have remarkably opposite values and character traits.”

“All right, Doc. Save it for court. And you think you can pull this off, Newkirk?”

The lawyer nodded. “I’m looking forward to making the case. Why, there’s never been such an argument presented in court. We could very well set a precedent. In fact, we shall do so simply by bringing it before a judge, whether we win or lose.”

“Well, winning or losing when you’re the same person doesn’t sound like good odds to me. What are they gonna do? Hang half of him?” Fat Jack puffed out his chest, sure that he’d made a valid point.

Newkirk frowned. “No, Sheriff, that’s not my strategy. I hope to convince the judge to absolve Mister Luken from the crime and commit him to a doctor’s care. This, per the M’Naghten Rule of 1843, which states ‘at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was laboring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.’ ”

Fat Jack rolled his eyes. “You lawyers. Spence! Go get Eddie and take him to the courthouse. The three of us will be there in a few minutes.”

Spence fetched Eddie and fastened a manacle onto the prisoner’s narrow wrists, which were crossed behind his back. The heavy iron bands were made for much bigger men, and Eddie straightened as the weight of them pulled down on his arms. The deputy herded Eddie out of the sheriff’s office and through the door. The miner looked exhausted. He had intentionally kept himself awake to avoid slipping into the stranger’s terrifying grasp.

Spence didn’t hold out much hope for the prisoner’s chances in court. The judge was an irritable man, and generally ruled on the harsher side of the book. Spence checked the manacle lock and gave Eddie a gentle pat on the shoulder.

“We’re just walking to the courthouse and

going in the front door, Eddie. Looky here what a beautiful day we got.” He usually transported prisoners through the courthouse’s back entrance but the door and frame were being painted. Somehow the job required two boys, each with a bucket and brush. It was nearly eight thirty, and the morning ore train whistle drifted down the street, three short blasts as it backed up to receive a dozen cars of raw ore. After chugging twenty miles to Bullionville, it would return to Pioche at the end of the day.

Eddie trudged ahead, shoulders drooped. They passed a fence with a scraggly rosebush entwined in its pickets. Eddie stopped and bent over to sniff one of the forlorn blossoms, then smiled. Spence cleared his throat. “Let’s move on.”

A crowd had gathered in front of the courthouse, waiting for admittance. News of Eddie’s trial had attracted a lot of local interest. Spence motioned for the onlookers to step back and let them pass.

Later, the deputy would say the movement was like that of a rabbit bursting from under a bush. With one quick shrug, Eddie pulled one of his hands free from the large manacle, and broke into a sudden, blurred flight—skirting the crowd of people and bolting across the street. He vanished between two buildings and Spence took off in pursuit just as the ore train blasted twice and its wheels began moving forward. Fat Jack’s voice boomed from behind. “He’s headed for the train! Catch him, Spence! Shoot him!”

The deputy caught glimpses of Eddie as he darted low and fast from one block to the next. He angled toward the edge of town, like he meant to intercept the train as it gained momentum and left Pioche. When Spence ran past the livery at the end of the street, he saw Eddie in the clear. He had shaken loose of the other iron cuff and slung the manacle aside. The engine was picking up speed, its pistons chugging faster and faster. Soon, it would be in the open and Eddie would be up-track to meet it with time to spare.

“Eddie!” Spence, still running, yelled over the sound of the approaching train. He was sure the miner couldn’t hear him but he didn’t want to shoot him in the back without a warning. Eddie reached the edge of the railroad bed and turned around. He looked directly at Spence, who was only fifty feet away, holding a Colt at arm’s length. They stared at each other for several seconds as the engine rounded the building, steam billowing from its stack. The deputy had a clear shot and they both knew it.

Spence aimed high on the torso and thumbed the hammer. Another second passed, and another. Fat Jack would be catching up soon. Eddie didn’t move even a finger—just kept staring. Spence began lowering the revolver, inch by inch, and uncocked the gun. Standing ten feet from the tracks, Eddie held up a hand in solemn thanks.

The space between Eddie and the train narrowed. Spence still held the Colt straight down at his side, waiting for the miner to crouch and jump onto a passing ore car when the time came. Instead, Eddie scrambled up onto the tracks. He laid himself down and stretched his body along the top of the rail farthest away, face up, arms and legs spread wide. The engineer sounded the steam whistle frantically.

“No! Eddie, no!” Spence shouted, and sprinted toward the tracks, knowing he couldn’t reach Eddie in time. The ore train’s brakes screamed against the rails, but too late to make any difference. A wall of hot air and dust pushed Spence back as the train thundered past.

Doctor Kent joined Fat Jack at a corner table in the Capitol Saloon. It was midafternoon and the place was quiet. “Well, Sheriff. So ends the remarkable story of Edarto Luken.”

“Yep. Didn’t end the way anybody figured. Crazy son of a gun. Knew I shoulda shot him first off. Might’ve spared him some misery.”

Both men stared at the table, coming to grips with the aftermath of Eddie’s last act. They would not soon forget the horrendous image. The ore train had accomplished what Eddie intended—rendering him, more or less, in half. For the first and final time, he had separated himself from the stranger.

“I hope he finds peace in the afterworld,” said Doctor Kent. “Poor chap deserves it.”

Fat Jack nodded. “I reckon he does at that. Say . . . I bought you a beer. You gonna drink it this time?”

The doctor smiled sadly. “Yes, I believe I shall. To Eddie . . .”

Fat Jack clinked his beer against the doctor’s. “To Eddie.”

Vonn McKee, Louisiana-born and descended from “horse traders and southern belles,” has worked as everything from country singer to riverboat waitress to construction project manager. Now based in Nashville, she turns her experiences and love of history into stories of the West.

THE DESERTER

BY LOREN D. ESTLEMAN

The hot Texas wind struck his face when he heaved open the door on its rollers, actually a relief after the oven hell of the freight car. Wind and streaming movement took his clothing in their teeth and shook it, the bandanna around his neck snapping viciously. He threw out his rucksack, then his saddle, and while they were still bouncing, braced himself with both hands, bent his knees, sucked in a gust of lung-searing air, and jumped.

He tucked himself tight, struck hard on his shoulder, and rolled, seeming to take on speed as he went, until he thought he’d go on rolling, flaying himself for a mile against stones, sand, and cactus until he plunged into the San Antonio River and drowned. When at last he fetched up in a ditch, he remained still, waiting for his breath to overtake him. He moved each of his limbs in turn, checking for broken bones. Reassured, he lay looking up at bright-metal sky. Given the choice, he’d have waited for the train to slow down some more before leaping, but he had not deserted his father’s ranch during the calving season, hopped a homely freight in motion, and roasted and starved all the way from Del Rio to be beaten by railroad bulls and turned over to a road gang so close to his destination.

At last he stumbled upright, took inventory of his rips and bruises, and hobbled back to reclaim his worldly goods. He found his hat and saddle, then the rucksack twenty yards west. Both were sound, the sack’s contents unspilled. Hoisting the saddle onto his shoulder and carrying the sack, he hiked toward the Cradle of Texas Liberty, regaining his footing with each step.

He was coming late to the ball, he knew. The first volunteers had arrived by horse, train, and shank’s mare weeks before, greeted by the brass band of the San Antonio Volunteer Fire Brigade playing a rousing version of a tune popular in the minstrel shows back east:

When you hear dem bells go ding-a-ling,

All join ’round, and sweetly you must sing,

And when the verse am through, the chorus all joins in,

There’ll be a hot time in the old town tonight.

No trumpets, drums, or cymbals greeted him at the station platform, where stood the train he’d left, hot and oily and panting like a winded buffalo bull. A gang of teamsters lugged kegs of powder, crates containing rifles, uniforms, and boots, cases of tinned goods, and sack after sack of grain from the freight cars.

A lounger in a straw boater and seersucker jacket stood aslant against a porch post, picking his teeth. Hicks asked him for directions. The lounger took out the splinter of wood, studied the masticated end, and pointed it at a wooden plank nailed to the station wall, painted with uneven letters. The sign read, THIS WAY TO CAMP OF ROOSEVELT’S ROUGH RIDERS. The newcomer touched the salt-and sweat-stained brim of his hat and followed the arrow painted at the bottom of the sign.

As he walked, shifting his burdens from arm to arm and back to relieve his muscles, other signs wrought as if by the same inexpert hand hung below more formal placards directing him toward Riverside Park, on the banks of a swift waterway winding through the biggest city he’d ever visited.

Another sign of recent manufacture, mounted on tall posts and straddling a lane worn by the tread of many feet, told him he’d arrived at Camp Wood. A tent large enough to shelter a circus sideshow stood at the far end of the lane.

Here, Spencer Hicks lowered his saddle and rucksack to the ground and took hold of one of the posts supporting the sign, as if to test its solidity and assure himself he hadn’t dreamt the whole odyssey.

/>

“Well, I’m here,” he said. “Now which way’s Cuba?”

“Delighted to meet you, son.” A burly young man in a buff uniform that fit him too well to have been issued by a quartermaster seized Hicks’s hand and wrung it till he thought blood would spit out of his pores. The man seemed to have more than his fair share of teeth behind thick mustaches. Gold-rimmed spectacles straddled his nose. He struck the Texan as a popinjay, but before he could form a solid opinion, the officer—for he wore the epaulets of a lieutenant colonel—turned to the man at his side, who looked younger even than he. “Leonard, this is the young man I told you about. His father ran my ranch in Dakota. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in sixty-three and his father fought with distinction in the Battle of New Orleans. His grand father served with Washington at Monmouth. We can expect fine things from this lad.”

“Perhaps. Heredity isn’t everything, Theodore. Isaac Newton’s father was an illiterate tradesman.”

Hicks said nothing; the wise course, in view of the fact he had no idea who Isaac Newton was. He stood at more or less attention, facing a desk in the sideshow tent that seemed even bigger than it had appeared from outside because it contained no other furniture except a homely crate on the floor. They were all standing.

Theodore, the man in glasses, adjusted them, registering slight annoyance at the other’s remark, though he said nothing; it seemed Leonard, the younger of the two, was his superior. Nothing about this war resembled the stories Hicks’s father and grandfather had told him. “Young man, tell me in as few words as possible what you have to offer this regiment.”

“Marksmanship.”

The other officer spoke. “Perhaps a few words more.”

“Name the thing and the distance and I’ll shoot it.”

Contention and Other Frontier Stories

Contention and Other Frontier Stories