- Home

- Hazel Rumney

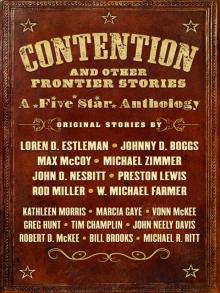

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Page 9

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Read online

Page 9

I threw extra feed to the chickens and the two pigs. They’d all get along fine until I got back. That I wouldn’t get back was not a thought I was willing to entertain.

In the tack room, I opened the wooden box disguised to look like a bench on the back wall. Ray had thought of the barn like a fort, much more defensible than the cabin. Here we kept the Sharps rifle Ray had used as a buffalo hunter, wrapped in oilcloth, and I knew he’d cleaned it just a week before. The walnut stock gleamed near as bright as the barrel. It wasn’t a practical weapon around the ranch, but like the barn, a last line of defense. Kansas had its share of outlaws, both white and Indian, and showing off a Sharps over the mantel was an invitation to trouble. A box of .50 calibers sat beside it and the .22 pistol I’d carried back in the day when I was a whore in Dodge City, just in case of an over-enthusiastic customer. Both weapons triggered memories we’d rather forget and storing them in the barn had helped with that. I’ve never been ashamed of my past, because that’s how Ray and I met. I hadn’t been in the game long, and he was just a kid, too, hunting buffalo. Neither of those professions were particularly palatable, but we’d both done what we had to. Both of us hard luck orphans, when we found each other, we found family we’d never had. We threw in together and never looked back.

I stuffed the .22 in my boot and the box of bullets into one of the saddlebags, filling the other one with hardtack, biscuits, water, and a flask of whiskey. I whistled for the colt who seemed happy to be saddled, at least for the moment. Poe danced about beside the colt, sure he was going as well, and he was right. Poe and Susie were orphan half-wolf cubs, near death when I found them. Ray had laughed and hugged me, saying, “Mary, you take in any stray you can find, just like you did with me.” Now, at close to 150 pounds, Poe was the gentlest, smartest, and most loyal dog I’ve ever known, just like his poor sister. I didn’t bother to pack food for him, as there wasn’t a rabbit born Poe couldn’t have for dinner.

One look was all I allowed myself, the sun rising behind the little cabin, lighting the worn timbers, and glistening on the dew of the grass. I sought solace in the only way I could and I was going to find it.

They’d gone south, by their tracks, which even I could see and Poe had no trouble scenting. They were probably headed for Oklahoma, not back to Dodge, thirty miles east and full of people who knew those horses had just been sold to us. They’d had a long head start and it was likely I wouldn’t find them today, even though I could travel faster. They were sloppy, the tracks ranging to and fro, as though the stolen horses knew they were being taken away from a safe haven and sought to turn homewards.

Even though it was only May, by noon the sun was burning through my hat and my hair was soaked with sweat. I stopped and chewed on some jerky underneath some cottonwoods and let the colt have a long drink from the creek. Poe wandered a bit, but when I got back in the saddle, he trotted up, ready to go. I loved that dog, and I’d loved Susie, too, like the children I didn’t have. I couldn’t allow myself to feel anguish over Ray or her, because I needed that hard ball of hatred that had centered in my chest to be my guiding star. Any other emotion would only slow me down or stop me from doing what I had to do. I thought of Hamlet, which Ray and I had just finished reading, Shakespeare being our only book, one I’d bought for a dollar from a peddler in Dodge. We’d had a Bible, but found Shakespeare to be a better guide to the human condition and truly the ways of the world and the things that could happen to people. “Revenge should know no bounds” was the line that kept repeating itself in my head, and a mantra that I now had set my course upon. Although it wasn’t simple revenge I was after. It was justice I sought.

By sunset, still having seen no sign of Seth, Ruben, or my horses, I decided to stop for a while, even though the colt was showing little signs of fatigue and was sure-footed even in the dark. I’d sleep for a time and perhaps go on in the night, catching them when they least expected it.

When I woke, the sun was already up and both Poe and the colt, hobbled but anxious, were bent over me. I’d been exhausted, by physical exertion and grief, both of which had taken their toll. I comforted them both, splashed water on my face, breakfasted on a hard biscuit and a swig of water, and we started on. So far, I hadn’t seen another human soul, only the hawks and ravens and an occasional coyote. Hopefully that would change soon, but there were only two humans I wanted to see and I hoped no one else would get in my way, from stray Indians that could kill me to settlers that would slow me down.

The day passed without either of those events and I decided to stop early. I hobbled the colt and didn’t bother to light a fire, falling asleep as soon as my head rested against the saddle I used as a pillow, Poe beside me, warm and snoring softly. This time when I woke, it was full dark and I saddled the colt and headed south, hoping to see some signs of a campfire in the darkness of the prairie night. This was my wish, as I didn’t want to come upon them during the day, which would be much to my disadvantage.

An hour later, Poe barked softly and I peered across the rolling hills, the nearly full moon giving me good access further ahead. A half mile away, near a rising knoll of rock outcroppings, there was the glow of a campfire. We crept closer, slow silent going, the horse, the dog, and I, and stopped on the rock-strewn hill above.

The horses were hobbled, four of them, including the two I sought, off to the side, while my two adversaries sat in front of the fire, passing a whiskey bottle back and forth. While conventional niceties dictated a dawn attack, I didn’t see any reason for niceties of any sort and no reason to get any closer. Besides, the firelight illuminated them just as well for my purposes. I took the Sharps from where I’d tied it to my saddle, set it atop a good-sized rock to use as a mount, and loaded a bullet. Ray had taught me well, hours of practice shooting the rifle just in case I’d ever have need to. He’d finally pronounced me proficient enough and now I hoped he’d been right.

Their voices carried in the still, clear night.

“We can sell these beauties for enough to set us up for months, Seth. I told you the minute I saw those two farmers walk away we were in clover, didn’t I?”

“Yeah, you were right, as usual,” Seth said. “But you ain’t the one with an arm tore up by some monster dog and a bullet from that bitch, Ruben. I need more than a half share, since I’m the one took the hurt gettin’ it.”

Ruben took a drink from the bottle. “Don’t make no difference. Thing is, it was my idea. I just took you along for the ride. You hadn’t shot the guy right off, we coulda killed them both in bed.”

I sighted the Sharps on the middle of Seth’s chest, took a deep breath, and pulled the trigger. He went down hard, the shot echoing off the rocks like a thunderclap. My shoulder felt like I’d been kicked by a horse but I reloaded and stared down at the campfire. Ruben had vanished, like a snake that crawls under a rock, and that was worrisome. Still, I hadn’t expected he’d sit there and be the next target. The easy part was over.

They couldn’t have known where the shot came from, but after a few minutes I got uneasy. There was no movement in the camp below but Ruben wasn’t going to wait to get picked off. He could be anywhere and the back of my neck prickled. The urge to sneak down there, finish things, and get my horses was offset by plain sense. I’d have to wait until dawn and I couldn’t do it exposed up here. I scrabbled backwards along with Poe. Taking the colt’s reins, we made our way further down to the flat, taking cover in some rocks and brush. Poe would tell me if Ruben was nearby. Lord, I was tired. Killing’s a weary business.

I surely was not expecting the shot when it came, buzzing just over my head. I flattened myself onto Poe’s back, his deep growls resonating through both of us, and the colt had wisely skittered away. Pale light filtered through heavy clouds and I looked around frantically, not raising my head, but I couldn’t see Ruben.

“Stay.” I wasn’t going to lose anyone else I loved. I took off my hat and Poe stared at me but didn’t move. I crawled on my belly behind the bi

ggest of the rocks to get some cover with a better vantage point, the Sharps clutched in my hand.

Another bullet cracked off the rock near my head. Where the hell was he? I ducked down and then I saw him, perched not far from where I’d been last night. It was way too close.

“Hey!” I yelled. “I just want my horses. Leave ’em and we’ll call it a draw.”

“Well, well. Little Missus.” He laughed. “Seth always had bad aim. I don’t.” His next shot sailed over my head. I should’ve killed this one first. He was a little smarter.

“What’d you shoot poor old Seth with anyway, a buffalo gun? Half that boy was gone. I’d like to have that Sharps, Missus. Maybe we can make a trade. ’Cause, by the time you miss me once, before you can reload, I’ll have you and your gun anyway.”

“What kind of trade?”

“How about I let you leave, and you give me the rifle? The horses don’t figure anymore, girl. You shot my partner, after all. I call it a good deal.”

I waited for a minute before I answered, my voice trembly. “All right then, mister. Deal.” I put the Sharps down in front of the rocks and retreated behind them. Poe remained motionless and I patted him on the head.

He came down the hill, a grin on his face, holding Ray’s Colt at his hip. “Come on out, honey, and we can shake on it.”

So I did. I shot him in the face with the .22 and watched as his blood leaked into the stony ground and until his heels stopped beating a rhythm to go with it. He wasn’t smart enough.

I left them both where they lay. Neither of them warranted my efforts at a burial, decent or otherwise, and I doubted anyone would miss them. Things can happen to people out here. I shooed off their horses and took my two. We were home the next night, all five of us, all safe in our respective beds. I take care of what’s mine.

Late summer, the prairie grass turned golden and the sunsets were something special. I sat beside Ray’s grave on the hill behind the cabin, Poe’s head on my lap, watching my horses in the pasture below. The mare was pregnant, and I’d had two stud offers already for my stallion. Word got around. I lay down on the soft grass and put my hand on my stomach. The baby kicked for the first time and I smiled. Ray had always wanted a boy.

An aficionado of Western history, Kathleen Morris lives and writes in the desert Southwest. Her novel, The Lily of the West, the untold story of Mary Katherine Haroney, known as “Big Nose Kate,” will be published by Five Star in January 2019. For more information, you can visit her website, www.kathleenmorrisauthor.com.

DARLINGS OF THE DUST

BY JOHN D. NESBITT

The man named Dunbar came to the town of Westlock, Wyoming, on a snowy November day. I was loading groceries into the wagon to take back to the ranch, and I first saw him when he was about three-quarters of a mile away, on the road that led from the north and became the main street in town. As I went back and forth from the store to the wagon, the rider came closer and became more visible. He was riding a blue roan and leading a buckskin packhorse, both dusted in snow as he was. The horses’ footfalls made but the faintest muffled sound on the carpeted ground, and with the snow swirling around them and the powder rising from their hooves, one had the illusion that the horses were not connected to the earth in the usual way but came roiling, with their master, out of the maw of the frozen North.

The rider drew up next to the wagon as I hefted a fifty-pound sack of beans into the bed. The air was cold—about ten degrees, I thought—and the thin, dry snow gathered on his black hat, his dark mustache, his brown canvas surtout, and his dark brown chaps, as well as on his saddle and on the canvas packs on the buckskin horse. Reaching up with a gloved hand, he brushed the snow from his mustache.

“Good afternoon,” he said.

“And the same to you.”

His dark eyes took me in. “Can you tell me where the Paradise Valley Ranch is?”

“Yes, I can. It’s about ten miles southwest of here.”

He blew a puff of breath through his mustache. “Might be a bit late in the day for me to find it at that distance.”

“Could be,” I said, “but the foreman’s right inside here. What do you need?”

“I heard they might have work.”

“You’d have to ask him.”

“Of course.” He studied me. “I would almost guess that you work there, too.”

“Good guess. I’m the cook. But maybe you figured that as well.” I pointed with my thumb. “The foreman’s name is George Clubb. He’s the fellow with blond, wavy hair, warming his hands at the stove.”

The newcomer smiled. “And your name, if I might be so bold?”

“Cyrus Fleming,” I said.

“J.R. Dunbar.” He swung down from the saddle, passed the lead rope from one hand to another, and held out his hand to shake. “Thanks for telling me what you know. Some people aren’t that helpful.”

I suppressed a smile. “I didn’t tell you much.” At the beginning, at least, I had prided myself on not telling him any more than he asked.

He gave me a look that expressed confidence and humor together. “You told me more than you had to, and more than you said outright.”

I wondered what I had told him without saying—that George Clubb didn’t mind letting someone else do the work? That the Paradise Valley Ranch was not a good place to work? That the ranch did not keep hired hands for long, and that was why a stranger might find work in November? I imagined that all of those truths were inherent in what I did and did not say to Dunbar.

I said, “I’ll be happy to tell you more, by saying even less.”

“You’re doing well,” he said. He tied his horses and went into the store.

I found out soon enough that Dunbar was not shy about asking questions, at least of me. As we were bringing in firewood the next day, he began with a statement.

“The big boss seems to keep to himself.”

“The owner? I suppose he does. He leaves quite a bit to his foreman.”

“His name is Wardell, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is. Prentice Wardell.”

“How long has he been here?”

“Four or five years.”

“Did he name this ranch?”

“Yes, he did. The ranch and the valley both, though the ranch had previous owners.”

Dunbar cast a glance toward the ranch house. “And what about the two girls he has working for him?”

He caught me off guard for a moment. Common bunkhouse hands did not ask about the girls, and I did not volunteer comments. But I had seen them—two sisters who swept in silence. In summer it seemed as if they spent all of their days with a broom and a dustpan, sweeping the ranch house, the veranda, the steps, and the stone walkway. Now in the cold part of the year, they swept the dust of winter inside and the dust of snow outside.

“They’re sisters,” I said. “Lucy is about thirteen, and Ophelia is about fifteen.”

“I could guess that much. Where do they come from?”

As I pictured the girls with their dusky complexions and straight, dull black hair, I wanted to say, as I had thought, that I imagined them as having materialized out of the dust. But I said, “According to the boss, he found them in New Mexico Territory. He picked them up off the street in Albuquerque, where they were abandoned, and he and his wife took them in.”

“Adopted, or just used as inexpensive domestic help?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never asked. All I know is what I’ve heard.” After I pause, I added, “Are you interested in them?”

Dunbar put one last piece of firewood in the crook of his arm, smiled, and said, “All things human are of interest to me.”

“Or, as the philosopher says, ‘Nothing human is foreign to me.’ ”

“I think that might be the way I first heard it. But time, and the company of cattle, dulls the memory.”

“I know what you mean,” I said. “An hour from now, I won’t remember we had this conversation.”

George Cl

ubb, Dunbar, and I were drinking coffee at midmorning. The two had done the morning chores of pitching hay to the horses and breaking ice on the troughs, and now they sat without saying much to each other. Rather than try to make conversation, I kept my own counsel as well.

A cold draft of air swept into the bunkhouse as the boss stepped inside. He closed the door behind him and paused, as if he needed to take stock of the room. He was wearing a fox-fur cap, a long coat made of coyote pelts, and a pair of padded leather gloves. He clapped his hands together, took off his gloves, and walked over to stand next to the foreman’s chair.

“George, you need to bring in more hay. We’re bound to get more snow at any time, and we can’t afford to run out.”

George nodded. “I was thinkin’ the same thing.”

The boss drew himself up to his full height. He was taller than average, and I had formed the impression that he liked to lean and loom over his men. Now he turned to Dunbar and said, “I’d just as soon you didn’t talk to my working girls anymore.”

Dunbar regarded him with a calm expression.

The boss waited a few seconds, and getting no answer, he said, “What business did you have talking to them, anyway?”

Dunbar’s dark eyes held steady. “I had the impression I had seen those girls somewhere before.”

The boss’s eyes tightened for a second. “I’d be surprised if you did. At any rate, you can leave them alone.” Turning back to the foreman, he said, “Bring in about three wagonloads. Go to the farthest haystack first.”

George gave a look of displeasure but said, “Sure.”

I knew that the summer crew had put up half a dozen haystacks at various places, each stack with a fence around it. The farthest one out was quite a ways from the ranch.

The boss continued. “I don’t think you’ll have time for more than one load per day, and you’ll want to carry a lunch.” He shifted in position to speak to me. “Cy, make them up something to carry with them.”

Contention and Other Frontier Stories

Contention and Other Frontier Stories