- Home

- Hazel Rumney

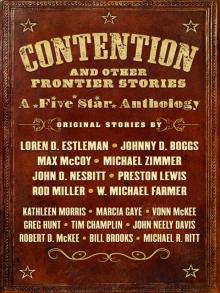

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Page 10

Contention and Other Frontier Stories Read online

Page 10

I pushed my chair from the table. “I’ll do that.”

As I rose, I heard the boss say, “What did you say your name was?”

Dunbar said, “This bein’ the first time I’ve spoken with you, I didn’t say. Not to you, at least. But as I told Mr. Clubb, my name is Dunbar.”

“Do you always give smart answers?”

“No.”

“Well, do what George tells you.” The boss nodded to his foreman, and putting on his gloves, he walked back out into the cold morning.

The boss came to the bunkhouse before sunrise the next day while the men were finishing breakfast. They had not gone out to do the chores yet, and they still had to unload the hay they had brought in at dusk, so I wondered why the boss appeared so early. In the cold part of the year, he did not venture out in the gray of morning.

Dressed again in his raiments of fox and coyote, he loomed over the table with the hanging lamp casting his face in shadow. He stood in a position that allowed him to face the foreman while he gave his shoulder to Dunbar.

“George,” he said, “I’ve decided we’ll put this first load up in the hay mow.”

George stopped with his fork a couple of inches up from the plate. “We haven’t done that before. Are you sure we even have the right equipment?”

“Of course we do. Everything came with the ranch. There’s an old set of tongs out where the field tools are. Everything else is in the harness room.”

“Do you know how to do it?”

“It’ll take all four of us. Two teams of horses—one on the wagon, one on the hoist. We have one man with each team, one man on the load, and one man up in the loft.”

“I’d think you’d want to have two men in the loft.”

“I thought you’d never done this before.”

“I haven’t.”

The boss took a calm breath as he pressed his gloved hands together, interlocking his fingers.

George spoke again. “Why do you want to go to all the bother, anyway?”

“I told you yesterday. I want to get in a good stock of hay.”

“Three wagonloads will fit where we always put it, on the ground floor.”

“For God’s sake, man, do you have to argue with me at every turn? I say we’re going to put the hay in the loft, and that’s what we’re going to do. So as soon as you get your grub in your bellies, get out there and feed the horses. Then get the tools together, and grease the track that the pulley runs on. By the time you’re ready, the horses’ll be fed, and we can get to work.”

He turned and walked away, without having taken off his gloves. A draft of cold air rolled in as he closed the door behind him.

George had resumed eating. With fried potato in his mouth, he said, “Seems like a lot of trouble to me. Have either of you done it this way before?”

I said, “Back on the farm, when I was growing up. The winters were wetter there, so we tried to keep as much of the hay inside as we could.”

“Build a good stack, and it sheds water.” He turned to Dunbar. “How about you?”

“I have some familiarity with it. But people do things differently from one place to another. We’ll see how Mr. Wardell does it.”

As I walked out into the ranch yard after putting the kitchen in order, a cold wind was moving the dust around above the frozen surface of the earth. The sky was gray and cheerless, and not much sound carried on the air. At the peak of the barn, George Clubb stood in the open doorway to the loft while Dunbar seemed to hang from the gable by one hand. On closer observation, I saw that he had one foot in a loop of rope hanging from the pulley as he held his left hand on the steel track that ran overhead. On his right hand he wore a gray wool mitten with which he was smearing dark grease onto the track. George held the can of grease with one hand and the door post with the other. When Dunbar needed another gob, he reached over while George leaned out with the can.

The boss’s voice sounded in back of me. “Don’t fall down and break your neck.”

I assumed he was talking to George, as he avoided Dunbar. Besides, I didn’t think he would have minded if Dunbar did fall and break his neck. He might even have wished for it.

George called back, “We’re almost done with this part.”

I turned to acknowledge the boss. He was wearing a knit wool cap, a coarse wool overcoat, and wool gloves—all in drab tones of gray. He reminded me of a painting I had seen of Russian soldiers trying not to freeze to death during the Napoleonic war. I thought he might be overdressed—not because of his fondness for matching outfits but because I had learned not to wear my warmest clothes in the early part of the cold season. Even in the dead of winter, one had to remember that the weather could always get colder.

“Cy,” he said, “I’m going to have you hold the reins on the wagon horses. You don’t have to do much. Just sit on the seat and keep ’em in place.”

“You don’t want me to pull them forward each time you raise a load?”

“No need to.”

“My father always did. In case the load spills. If it lands on the wagon, it can spook the horses.”

“No need to. We’re not going to drop anything.”

I wondered if he or someone else was going to stand in the wagon, but I didn’t ask. I would see soon enough. I followed him to the barn and stood outside as the men finished the task above. Dunbar tossed the mitten into the loft and held onto the rope with both hands. I saw now that the rope was doubled. With another rope attached to the pulley, George tugged and disappeared, moving Dunbar into the loft like a quarter of beef or a block of ice.

At ground level, I stood by as Dunbar wiped his hands on a cloth. Neither of us spoke. I watched Dunbar in an absentminded way as the boss and George talked in an undertone a few yards away.

As Dunbar finished wiping his hands, I noticed something I had not seen before. In the palm of his right hand, he had a dark spot that looked as if he had been burned there. He did not seem to make an attempt either to hide it or to show it. Rather, he waved his hand as people do after washing and drying their hands.

The moment passed, and George spoke as he walked toward us. “Cy, you’ll work the wagon. I think you already know that. The boss will be in charge of the other team, and I’ll be in the loft.” Then, as if he, too, would prefer to avoid Dunbar, he turned partway and said, “You’ll work the load. Make sure you get a good grab each time, and stay out of the way.”

I felt a sense of dread building as George and Dunbar brought out the horses and hitched the first pair to the wagon. I did not think that the boss and his foreman had conspired to dump a load of hay on Dunbar, but I knew something could go wrong. George was not familiar with the process, and I was not convinced that the boss knew much about it, either. Dunbar had suggested that he knew something, but the boss wasn’t going to put him in charge. Neither was he going to put me, an old gray-haired man with ruddy cheeks and a round girth, even though I had more experience with the work than at least two of the others.

Before long, I discovered how much the boss did not know about raising the hay. He wanted to use the second team of horses in front of the barn in order to lift the load. Dunbar looked on and said nothing, but I had to speak up.

“Excuse me,” I said, “but I’ve never seen anyone haul the hay up that way. You’re supposed to run the rope up to the trolley and out the back of the barn. Then when you get the load to the height where you want it, you hit the trip and pull the load into the barn where you stack it. Then the man running the forks pulls everything back so he can grab another load.”

The boss said, “You mean the tongs.”

“I learned to call them the forks, but that’s a small matter.”

George spoke to Dunbar. “What do you know?”

“I learned to call them forks, too. And, yes, you have to pull it from the other end. Furthermore, I didn’t see a trolley in the harness room or when I was up there. You’re going to have to find one somewhere, or none of this is go

ing to work.”

“Then what’s the pulley for?”

Dunbar shrugged. “For hoisting things up there, I suppose. Smaller things. But not for any systematic method of moving hay up into the loft.”

“Why didn’t you say something earlier?”

“No one asked.” Dunbar put on his coat, a buckskin-colored canvas work coat, and took a pair of yellowish leather gloves from the pocket. He put on the gloves and assumed an air of waiting.

The boss pulled off his wool cap and slammed it on the ground. “By God, I don’t like the way the two of you just waited to make a fool of me.”

The boss picked up his cap and stomped away. What thoughts went through Dunbar’s mind as he watched, I do not know. As for myself, it occurred to me that the boss would have a much harder time dropping a load of hay on someone from the other side of the barn.

The hay loft went unoccupied, then, and the three wagonloads fit in the ground-floor area as George Clubb had said they would. The boss kept his distance, and once the hay was in, George absented himself by going to town.

Dunbar lingered over coffee and a serving of apple pie I had made. When a feeling of there being only two of us in the bunkhouse set in, he said, “I sometimes wonder about the boss’s wife.”

“Mrs. Wardell?” I asked.

“Yes. I wonder if they’ve had children of their own, or if she has taken any kind of interest in the two working girls.”

“I’ve never heard of their having children,” I said, “though they might be old enough to have children who have grown up and gone out on their own.”

“You say they’ve been here four or five years?”

“About that. I’ve been here for two years, so I don’t know for sure.”

“What’s her name?”

“Mrs. Wardell? I believe it’s Nancy.”

“I haven’t seen her.”

“She doesn’t go out much. Even in two years, I’ve seen her but a few times. Thinking back to your earlier question, or comment at least, I don’t know that she has any maternal interest in the girls. She doesn’t turn them out with their hair braided or in cute outfits. They’re always rather plain-looking.”

Dunbar gave a mild shrug. “It’s hard to know about other people.”

“They do live out of the way. And even here, they keep to themselves.”

“Have you ever talked to those girls?”

“No, I haven’t. I’m sure they know how, though they’ve always seemed silent. Even at a distance, I haven’t seen them talk.”

“Oh, yes,” said Dunbar. “They can talk. He hasn’t cut their tongues out, like the king in the story.”

“I don’t remember his name,” I said, “but the girl’s name is Philomela. She becomes a nightingale in one version of the story and a swallow in another. And she has a sister as well.”

“That’s the story I was thinking of. The nightingale.”

The wind was blowing as it can only blow in November—cold and bleak and relentless, day and night, whining at the eaves of the bunkhouse and driving bits of dead grass through the air. I was humming a song to myself and thinking that it was no day to be working outside except for the most pressing chores. Yet the boss had George Clubb and Dunbar working behind the barn, on the windward side. At a little after eleven in the morning, the foreman barged into the bunkhouse and told me they needed my help.

I took off my apron, put on a coat and a tight-fitting winter cap, and followed him across the yard and around the barn. There I saw where he and Dunbar had cleared a path by moving old fence posts, coils of barbed wire, scraps of iron, and twisted sheets of metal. The sheet metal was weighted down with fence posts, and I was glad not to have to move it in such a strong wind.

One object remained in the way, a rusty iron structure the use of which I did not recognize. It consisted of a thick frame about four feet high with a shaft and gear wheels mounted inside.

I tipped my head into the wind, holding onto my cap, and said, “What are we doing?”

“This thing’s in the way.”

“I can see that. You don’t expect the three of us to pick it up and move it, do you?”

“No. I want to tip it up and put a skid under it.” He pointed to a sled about five feet wide and eight feet long.

I looked up and down the pathway they were clearing. “Has the boss not given up on his idea of putting the hay into the loft?”

“He didn’t say.”

For a moment I was amused by the thought of the boss trying to save face, as it seemed to me, after having his men pile junk in the way for years. My reverie ended when George said, “Here he comes. You can ask him yourself.”

I turned to see Prentice Wardell marching into the wind, dressed, as it had seemed to me before, like a Russian soldier. His face was clouded with anger, and his eyes were hard.

“You!” he shouted at Dunbar. “Get over here!” He made a motion with his arm and pointed at the ground in front of him.

Dunbar did as he was told, carrying a six-foot iron pry bar. He held it upright like a pikestaff as he came to a stop and rested the end on the ground. He was wearing a short-billed gray wool cap instead of his usual black hat, and he looked as if he could have been a vassal to a feudal lord.

“I told you I didn’t want you talking to my hired girls.”

Dunbar’s eyes held steady as he said, “This country has laws and rights. You can’t hold somebody in bondage, and you can’t restrict other people’s freedom of speech.”

“Well, aren’t you the good citizen?”

“I might be.”

“You can do it somewhere else. I want you off my ranch. Now.”

Dunbar hefted the iron bar, and Wardell flinched. As Dunbar leaned the tool against the iron structure and turned halfway, the boss pulled an old sock out of his coat pocket. The toe of the sock swung with weight, and I could not believe the boss would try to sap Dunbar with such a paltry weapon.

I was right. He turned to the foreman and handed him the sock.

“George, here’s his pay. Give it to him when he’s packed and ready to go.”

“Can we finish with what we’re doing here?”

“I said now, and I mean it.” The boss turned and walked away.

“I guess that’s it,” said George. He hit the iron frame with the heel of his hand. “We’ll take care of this son of a bitch some other time.”

Dunbar had the blue roan saddled and the buckskin packed in less than an hour. The wind was blowing the horses’ tails in strands when he stopped at the bunkhouse door and I stepped out to say goodbye.

He was wearing his black hat and brown overcoat, and he stood in front of his horses, holding the reins and the lead rope in his left hand as he held out his right hand to shake. “So long, Cyrus.”

“It’s been good to know you,” I said. “Keep the wind at your back.”

“Can’t always.” He put his horses into position, and with the lead rope in one hand, he pulled himself aboard with the other. He tipped his head so that the wind would not carry away his hat, and he turned his horses north toward town. The wind blew their tails sideways as they trotted away, and I thought I had seen the last of Dunbar.

I was wrong.

At about ten the next morning, with the wind blowing as before, motion in the ranch yard caught my attention. I looked out the bunkhouse window to see Prentice Wardell hurrying to the barn with the two silent sisters. He had each one by the upper arm, and they showed no resistance. As the three of them disappeared into the barn, Dunbar rode into the yard.

Ah-ha, I thought. The boss has been keeping a lookout.

Dunbar had both of his horses. He rode up to the hitching rail in front of the bunkhouse and dismounted. As he tied the horses, I saw that the buckskin had a riding saddle instead of the usual packsaddle.

I opened the door and stepped out.

Dunbar said, “I thought I saw Wardell headed for the barn with the two girls.”

“Yo

u’re right,” I said.

“That might make things more difficult.” He took off his coat, hung it on the saddle horn, and settled his black hat on his head. He was wearing a gray flannel shirt and a charcoal-colored wool vest, buttoned snug. His dark-handled revolver hung in plain view.

He walked across the ranch yard, and I followed at a distance of ten paces. Fifty feet from the barn, he stopped. The doors to the loft were open, and Prentice Wardell stepped into view. Like Dunbar, he was not wearing a coat and had a pistol at his side. Next to him stood Ophelia, the older of the two sisters, with a rope around her neck. The rope led up to the pulley and back into the barn.

Dunbar spoke loud and clear into the wind. “I’ve come for the girls, Wardell.”

“You’ll do nothing of the sort. Take them God knows where and do God knows what with them.”

“Your righteousness is noteworthy, but you should give it up. I’m taking these girls to town.”

“You are not. If you don’t turn around and leave, I’m pushing this one off the ledge.” Wardell put his hand behind Ophelia’s back, and the girl trembled.

“The law’s going to get you one way or the other. Causing a girl’s death would not be—”

“I said leave.”

“I’m taking these girls, and the law will be coming for you. You’ve kept these girls against their will, and you’ve done things that no judge or jury will tolerate.”

Even with a small audience, the public nature of the accusation could be felt. It hung and spread in the ranch yard like a chill.

Wardell’s face was bunched in anger, and his voice pierced the air. “I hate you!” he shrieked, as he pulled his pistol and fired.

Dunbar drew his gun in a smooth motion as the bullet whistled past him and spat into the ground at my left. Raising and aiming with the hammer cocked, Dunbar fired.

Prentice Wardell dropped his pistol and pitched forward. He fell headlong, like the bad angels who were cast out of heaven in the great poem, and he landed with a thud in the dust.

Contention and Other Frontier Stories

Contention and Other Frontier Stories